New Method for Manufacturing the Elusive Green LED with Higher Efficacy

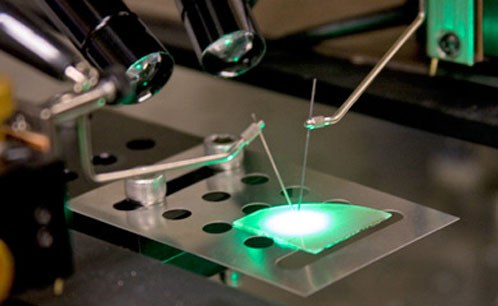

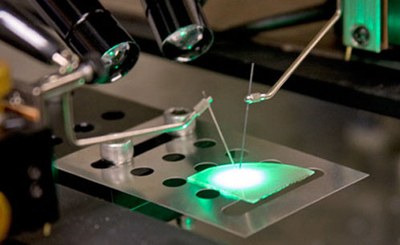

Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have developed a new method for manufacturing green-colored LEDs with greatly enhanced light output.

The research team, led by Christian Wetzel, professor of physics and the Wellfleet Constellation Professor of Future Chips at Rensselaer, etched a nanoscale pattern at the interface between the LED’s sapphire base and the layer of gallium nitride (GaN) that gives the LED its green color. Overall, the new technique results in green LEDs with significant enhancements in light extraction, internal efficiency, and light output.

The discovery brings Wetzel one step closer to his goal of developing a high-performance, low-cost green LED.

“Green LEDs are proving much more challenging to create than academia and industry ever imagined,” Wetzel said. “Every computer monitor and television produces its picture by using red, blue, and green. We already have powerful, inexpensive red and blue LEDs. Once we develop a similar green LED, it should lead to a new generation of high-performance, energy-efficient display and illumination devices. This new research finding is an important step in the right direction.”

Sapphire is among the least expensive and widely used substrate materials for manufacturing LEDs, so Wetzel’s discovery could hold important implications for the rapidly growing, fast-changing LED industry. He said this new method should also be able to increase the light output of red and blue LEDs.

Results of the study, titled “Defect-reduced green GaInN/GaN light-emitting diode on nanopatterned sapphire,” were published last week in the journal Applied Physics Letters, and are featured in today’s issue of the Virtual Journal of Nanoscale Science & Technology, published by the American Institute of Physics and the American Physical Society. The paper may be viewed online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3579255

The research program is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) Solid-State Lighting Contract of Directed Research, and the National Science Foundation (NSF) Smart Lighting Engineering Research Center (ERC), which is led by Rensselaer.

LED lighting only requires a fraction of the energy required by conventional light bulbs, and LEDs contain none of the toxic heavy metals used in the newer compact fluorescent light bulbs. In general, LEDs are very durable and long-lived.

First discovered in the 1920s, LEDs – light-emitting diodes – are semiconductors that convert electricity into light. When switched on, swarms of electrons pass through the semiconductor material and fall from an area with surplus electrons into an area with a shortage of electrons. As they fall, the electrons jump to a lower orbital and release small amounts of energy. This energy is realized as photons – the most basic unit of light. Unlike conventional light bulbs, LEDs produce almost no heat.

The color of light produced by LEDs depends on the type of semiconductor material it contains. The first LEDs were red, and not long thereafter researchers tweaked their formula and developed some that produced orange light. Years later came blue LEDs, which are frequently used today as blue light sources in mobile phones, CD players, laptop computers, and other electronic devices.

The holy grail of solid-state lighting, however, is a true white LED, Wetzel said. The white LEDs commonly used in novelty lighting applications, such as key chains, auto headlights, and grocery freezers, are actually blue LEDs coated with yellow phosphorus – which adds a step to the manufacturing process and also results in a faux-white illumination with a noticeable bluish tint.

The key to true white LEDs, Wetzel said, is all about green. High-performance red LEDs and blue LEDs exist. Pairing them with a comparable green LED should allow devices to produce every color visible to the human eye – including true white, Wetzel said. Today’s computer monitor and television produces its picture by using red, blue, and green. This means developing a high-performance green LED could therefore likely lead to a new generation of high-performance, energy-efficient display devices.

The problem, however, is that green LEDs are much more difficult to create than anyone anticipated. Wetzel and his research team and investigating how to “close the green gap,” and develop green LEDs that are as powerful as their red or blue counterparts.

For more information on the Wetzel’s research at Rensselaer, visit:

- Greenlighting a Green Future

http://green.rpi.edu/archives/greenleds/index.html - In Their Own Words: Christian Wetzel on Green LEDs

http://blogger.rpi.edu/approach/2009/09/01/in-their-own-words-christian-wetzel-on-green-leds/ - NSF Smart Lighting Engineering Research Center

http://smartlighting.rpi.edu/ - Rensselaer Center for Future Energy Systems

http://www.rpi.edu/cfes/ - Rensselaer Future Chips Constellation

http://www.rpi.edu/futurechips/index.htm