Tech-Talks BREGENZ - Dr. Maja Grubisic, Researcher, Free University Berlin & Leibniz-Institute

Awareness of the ecological impact of technologies is becoming more important since climate change due to industrialization cannot be denied. LED lighting is one of the technologies that is deemed as a contributor in helping to reduce the impact caused by wasted energy. Unfortunately, light pollution, due to inefficient energy usage, is not the only problem. Besides the more recognized pollution from pesticides and chemical pollutants, light pollution also disturbs ecology and wildlife. Dr. Grubisic, Researcher at the Free University Berlin & Leibniz-Institute, has been working on this problem for more than five years now. She has written an article, also in this issue, concerning this. At the LED professional Symposium she was also good enough to grant this interview, providing some background information, explaining why light pollution is such an issue in biology and why this topic should be of concern to all of us.

LED professional: Thank you very much for taking the time for this interview. We'd like to take the opportunity to talk about what you called "The dark side of the light" in your lecture. But maybe we could start with a short descripton of yourself. Where do you work and what are your main activities?

Maja Grubisic: Thank you for inviting me and giving me the chance to talk about this important topic. I am a biologist and work at the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin. I started working on the topic of light pollution five years ago. I came to the institute when I started working on my PhD, which focused on the ecological impacts of Artificial Light at Night. Currently I am continuing with my research as a post-doc. The group that I'm working in has been active in research of light pollution for more than ten years and we work to a large extent with aquatic organisms - fish, aquatic insects, and also algae that are in the base of aquatic food webs. And we also study terrestrial ecosystems and the links between the two.

LED professional: What kind of institute is this?

Maja Grubisic: It's a biological and ecological institute, Germany's largest research centre for freshwaters, so we cover a wide range of topics dealing with freshwaters and fisheries, trying to understand how processes in nature work, and we also look at different effects of humanity on the environment. So our research goes beyond aquatic ecosystems and explores interactions of ecology with society.

LED professional: Does your position as a researcher involve looking at how harmful light can be to the environment?

Maja Grubisic: Yes, my main responsibility is doing research. I study ecological impacts of light pollution on different organisms, mostly invertebrates, like insects and microorganisms from aquatic ecosystems. That is my current expertise, but the group I work in covers a range of different organisms. LED professional: So your focus is on the influence of light on the ecosystems. Maja Grubisic: Yes. We are also members of big international networks that include experts not only from biology and ecology, but also physicists, astronomers, lighting designers and social scientists interested in how people perceive artificial illumination. We communicate across different disciplines and try to convey the importance of this topic to a wider audience and society, in general.

LED professional: What does this research look like? Do you do research on individual animals or do you do field tests by counting animals, for example?

Maja Grubisic: We do both studies in the laboratory and in the field. So, for example, we have installed street lamps in the areas that were previously dark. So they would be in rural areas, away from the disturbances of the cities, where natural darkness is still preserved. We would switch on the street lamps in the evening and switch them off in the morning and over time we would collect insects that move in these areas - in illuminated ditch that is next to the field site - and the grassland. We count the insects and identify different species. And over time we compare if there are any differences between the illuminated fields and the control fields.

In the laboratory we try to simulate conditions that are present outside in light polluted areas, so we use light sources that are also used in outdoor illumination, and we apply light intensities and light conditions to mimic those present in the cities. We don't work with very high light intensities, like in horticulture, but we rather look at low light intensity present at the street level or away from the light sources comparable to sky glow. And then we also mimic natural daylight rhythms and apply low level of artificial light during the night and study effects on different, individual organisms and their physiological processes, behavior, biological rhythms and other aspects.

LED professional: How does light influence insects or other animals?

Maja Grubisic: Light is a very important source of information for all living beings. This is the case because, in nature, light regimes have been stable for a very long time. So these dark and light cycles are one of the most stabile environmental changes and many organisms, throughout evolution, have learned to rely on light patterns. Almost every living being has circadian rhythms and they adjust their behaviors and inner processes to the time of the day based on the information that light provides. What we see is that biological rhythms are influenced by artificial light at night in many animals and in insects. Another important aspect is that a lot of species are active at night and they evolved to be active in the darkness. They are very sensitive to light and introducing artificial light into the night can disrupt their natural behavior. The most obvious and most well known phenomenon is that light attracts insects, but it can also disrupt the way they feed and reproduce and communicate with each other. For example, fireflies communicate by flashing light in the dark - this allows them to find each other and reproduce. So there are many ways in which light can influence the environment.

LED professional: The human circadian rhythm is mainly influenced by blue light and high intensities. Is that the same for insects?

Maja Grubisic: There are not many studies on circadian rhythms in insects, much more is done in birds and fish. Blue light is indeed the most powerful part of the spectrum that influences biological rhythms but low light intensities can already have an effect. An example of extreme sensitivity to this is what we find in fish: they show melatonin suppression already at 0.1 lux at night. But with fish, when we compare the same light intensity of different colors, blue light seems to have the least effect. So in the spectral composition, it is just the opposite of that of other organisms.

LED professional: I also heard that this is true in connection with insects and street lights and so they shouldn't use bluish light, but rather go to warmer color temperatures.

Maja Grubisic: The impact of blue light on insects is maybe less based on the biological rhythms and melatonin suppression, but rather it is based on the amount of attraction. Their visual systems are very sensitive to UV light and blue light - so in general - shorter wavelengths. For this reason, a high amount of light in this range of the spectrum will be more attractive to insects.

Circular enclosures to study effects of skyglow (simulated by very low-level LED light at night) on lake ecosystems, including fish, invertebrates and algae. Researchers take samples at night before starting experimental illumination (Credits: Andreas Jechow)

Circular enclosures to study effects of skyglow (simulated by very low-level LED light at night) on lake ecosystems, including fish, invertebrates and algae. Researchers take samples at night before starting experimental illumination (Credits: Andreas Jechow)

LED professional: Oh - so it is the blue light but it isn't the circadian rhythm.

Maja Grubisic: Yes - the same light, but a different reason.

LED professional: Is there a difference between the nocturnal and diurnal insects?

Maja Grubisic: There are around one million different species and each has its own evolutionary history. Among the different species, we find different photoreceptors in their eyes. Most commonly, they have three photoreceptors that are sensitive to the UV, blue and green part of the spectrum. But I'm sure there are exceptions.

LED professional: One idea, as mentioned before, is to go to warmer color temperatures, but what about shaping the spectrum of an LED for certain areas?

Maja Grubisic: Depending on the biological value of the area or the presence of endangered or protected species, it might be a solution to design the lights that are suited to the sensitivities of these species. It's not only about insects, though. A lot of other organisms live in nature and in general, the rule is to try to use the warmer temperatures. But areas close to water might have different regulated lights to those that are close to a forest or in areas where we know there is a species conservation that we particularly want to encourage. For example, amber LED lights along the coasts are less distractive for marine turtles that nest on the beaches. And for areas with large numbers of bats, reddish lights would be a better option.

LED professional: Can you tell us a little bit about the effects of light on animals and plants that live on or in the water?

Maja Grubisic: The research on waters is still a bit behind compared to studying effects of light pollution on land. But we have more and more evidence coming from both freshwaters and marine systems and when it comes to plants or microscopic algae, this is one of my fields of expertise. Algae are one of the groups that have been studied the least when it comes to waters. They are very important in aquatic ecosystems because they provide food for aquatic insects and fish, so they are a source of energy; a basic source of energy in the food chain. And if changes happen at this level it can easily reflect on other aspects of the ecosystem. What we found is that proximity of streetlights to water disturbs the growth of algae - which is the opposite of what we expected. We all know that plants like light, they use it for photosynthesis but it seems that this low light level - not giving enough energy for photosynthesis and occurring at an unnatural time - imposes stress on the growth of algae and actually results in an opposite effect. This could mean less food for fish and aquatic insects.

When it comes to the insects themselves, we know that they emerge in higher numbers from waters that are close to the lights and they are attracted to these lights. So in a way, material and energy gets taken from the water into the terrestrial ecosystem, and this change of energy fluxes could change the balance of these connected ecosystems. Water is never just isolated in the landscape. In nature, these processes are connected.

So far, in water, most of the research focuses on fish. Fish change their behavior around the lights. In the seas, for example, we see that some species benefit from the light because they are visual predators and they see their prey better. Then the smaller species swim away and try to hide and don't look for food like they would normally do. So these changes in behavior at different levels of the food chain can also disturb the ecosystem balance.

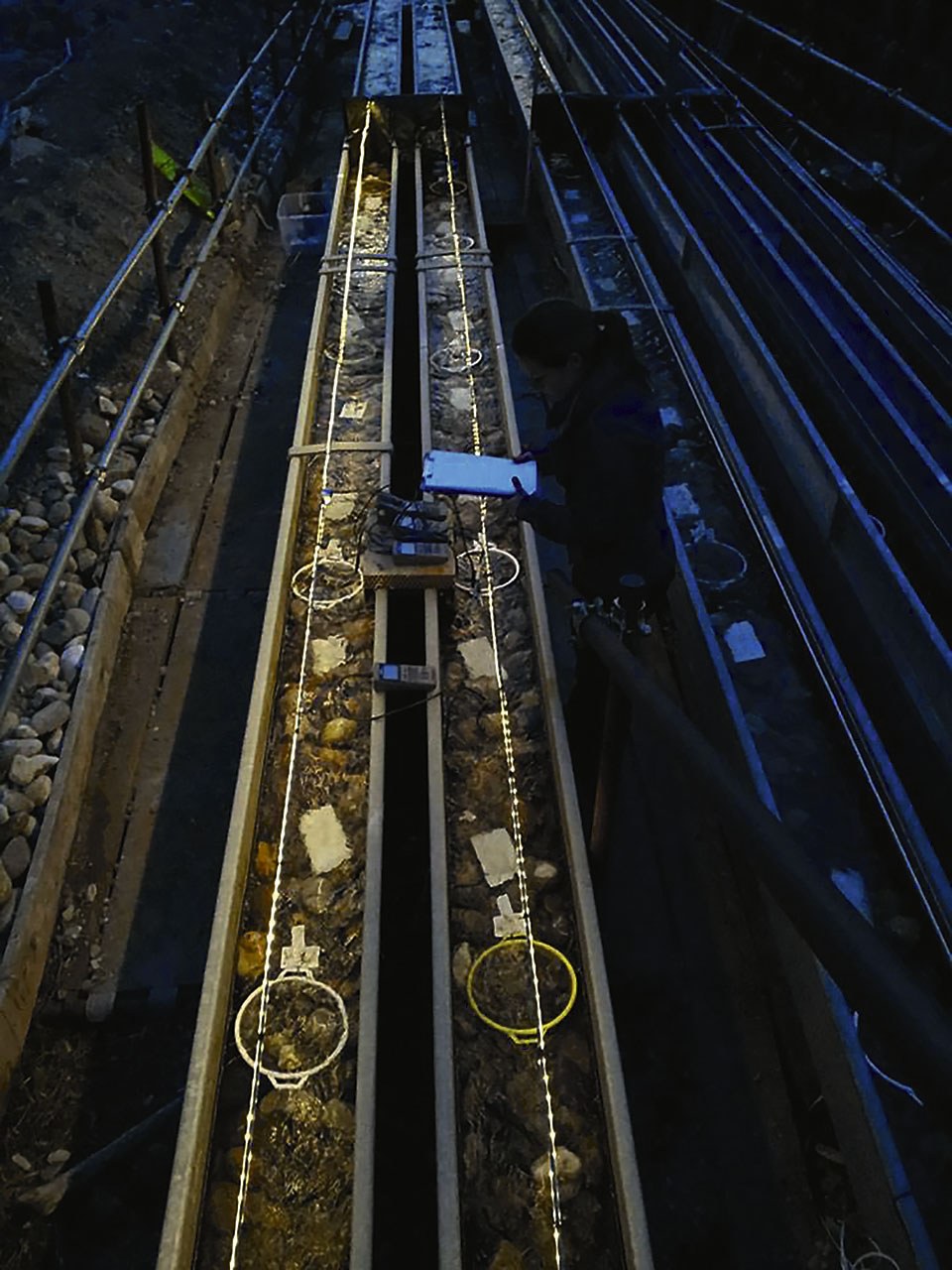

Night measurements during a light pollution experiment in an outdoor, stream-side experimental system, to study effects of low-level LED light at night on stream biota (invertebrates and algae). Such semicontrolled experimental systems that allow for replication and partial manipulation of parameters of interest are invaluable in ecological research (Credits: Alessandro Manfrin)

Night measurements during a light pollution experiment in an outdoor, stream-side experimental system, to study effects of low-level LED light at night on stream biota (invertebrates and algae). Such semicontrolled experimental systems that allow for replication and partial manipulation of parameters of interest are invaluable in ecological research (Credits: Alessandro Manfrin)

LED professional: When I look at the general message of the press, it seems like they want to blame the LED for everything. They say it's bad for animals, humans and plants - unless we're talking about horticulture. What is your opinion? Do you see any positive effects of the new technology?

Maja Grubisic: I don't think that LEDs are bad in and of themselves, but the way we use them may be bad and it definitely could be improved. The problem with LEDs is their bluish spectrum and that they are used everywhere now. It is cheap technology, widely accessible to consumers, and what we see now, based on recent studies, is that people tend to use more and more light because it is so cheap. I think that these are two problematic aspects of the LEDs. On the other hand, I think that the flexibility of this technology will allow for customized solutions. One solution is to optimize the spectrum, moving towards minimizing the blue emissions. Another thing to improve is directing the light and using full cut-off luminaries in order to avoid glare. To eliminate the excess light above the surfaces that need to be illuminated. And to use beaming and timers and motion sensors to adapt lighting scenarios to the needs and purposes of the light -these are also promising approaches. Any measure that reduces waste of light will also reduce light pollution, potential ecological effects of artificial light at night and save energy costs.

LED professional: In connection with obtrusive light - we often hear that we don't see as many stars as we used to. So this could be improved by directing the light downwards.

Maja Grubisic: Yes, and also adjusting the illuminance levels so the light doesn't bounce back up into the sky.

LED professional: Does the direction of light or the waste of light play a role with terrestrial animals?

Maja Grubisic: The waste of light certainly increases the size of areas where light can have an impact. When it comes to direction, insects are still attracted to the light even if it is directed downwards, but the glare has an impact. Shielding and reducing glare makes light itself less visible to insects. Based on the modeling studies it seems that the attraction range of one lamp to the insects, can reach up to 130 meters. For animals that move through the landscape at night, the more lights that are there, the more chance there is that the animals will come into the attraction range.

The main thing that we try to communicate to the public is the responsible use of lighting. This means directing light to where it is needed instead of wasting it and spreading it around. The next thing is only use the amount that is needed and not brighter, and lastly, to use light only when it is needed. An example of this may be that we have nice, decorative lights in the garden and they are on all night, even though there is nobody there to see them. That is a huge waste of light and can be a major disturbance for wildlife in the garden.

LED professional: Is there a difference between the measures being taken (dimming and shielding) and the effects they have on flying animals and terrestrial animals? Is there research going on for this?

Maja Grubisic: Some studies on insects compared different measures, for example manipulating spectra, dimming and switching off lights at certain times during the night and they found that the light still has an effect. So it seems that eliminating effects of artificial light at night is not really possible without abandoning its use overall. But we can minimize its impacts by avoiding it if it isn't necessary.

LED professional: What about measures like education or ideas of making "Dark Zones" - that are only illuminated when they are occupied by people.

Maja Grubisic: Of course, it is very important to educate people, especially to increase awareness that light has an influence on nature and other organisms as well as on ourselves. Many are still not aware of these issues and still more can be done to improve this. There are many activists involved in spreading these messages, many come from astronomer communities. There is also the International Dark Sky Association - IDA - that is based in the U.S. This association promotes the value of darkness. They work on getting the idea across that darkness has its value in nature and that it should also have a place in our lives. They also work on establishing "dark sky" parks in areas with little light pollution where people can go to look at the stars and enjoy the view of the night sky. I think we are becoming more and more disconnected from darkness, and it would be good to educate people they don't have to be afraid of the dark and that darkness should have a place in our lives.

LED professional: It must have been around fifteen years ago that I heard the first lecture on obtrusive light and I don't think that over the last fifteen years there has been a big increase in awareness of it. Why do you think that is?

Maja Grubisic: The interest in the scientific community was definitely there fifteen years ago but it wasn't the focus of their work. But now, over the last couple of years, it is becoming one of the hot topics. I wondered about it myself, but it's similar to what I've observed while attending this conference. This is the first industry-focused lighting conference I've attended and it's the first time I've heard about human centric lighting. One of the points raised on a panel discussion was that human centric lighting was a concept that was also mentioned fifteen years ago and it's still not on the market and people outside of this industry still don't know about it. In addition to talking to each other about these concepts inside our communities we should also spread the word outside to other industries and public.

LED professional: Coming back to the insects: you can read in all kinds of media, not just scientific papers, that the number of insects is rapidly decreasing. Some are saying that there are up to 90% less insects today than there used to be. I'm sure that there are multiple reasons for this phenomenon, but how much do you think lighting has played a role in it?

Maja Grubisic: We know that insects are declining from several locations and there is no clear answer why. Agriculture, pesticides, climate change and habitat destruction are considered to be the main reasons. One of the most recent reports on insect declines came from Germany last year. Researchers looked at trends in insect populations in protected areas across Germany, in areas that are supposed to have little human influence. In these protected areas there is no use of herbicides. Habitat change, also whether and climate change explained part of the decline. But a large amount of variation in the data could not be explained by all these commonly considered factors. So we looked at the locations of these sites and what we noticed was that most of the locations were in areas that experience high night sky brightness. Much higher than what natural light would be. These protected areas are relatively small and they are surrounded by agricultural fields and urban structures. The light spreads from the cities is in the form of sky glow and influences the area around them. We don't have clear data that shows that insects are declining because of light pollution but together with the other stress factors they endure, light pollution is definitely another form of imposed stress. This is why it must be considered as an influential factor in the future.

When it comes to moths - there we see a link between the population trends and their behavior towards light at night. We have seen from several different countries that there is a decline in moths and a very recent study done in The Netherlands shows that the biggest declines are in those species that are attracted to light at night. So this clearly indicates that light pollution is a significant factor in moth declines.

Dr. Grubisic speaking at LpS 2018

Dr. Grubisic speaking at LpS 2018

LED professional: Do you know of any research that considers the light level?

Maja Grubisic: Identifying a minimum impact threshold is a big question in this type of research and we don't have these values yet. The values depend on the lamp itself and the organism itself and their sensitivity throughout the year. It also differs from season to season depending on their biology. But maybe one of the reasons that we still don't have these thresholds is the exceptional sensitivity that we observe in more and more experiments, where we find effects even on very low light levels. The experiment that I just finished before coming to this conference is related to algae in waters where I tried to identify the minimum amount of light that will have an impact so that I can say - okay, lower than a certain level is safe, at least where algae is concerned. I did a laboratory study with a range of different intensities of white LED at night and I see the same response, no matter if it's 20 lux or 10 lux or 1 lux. All of them influence the growth of algae, so the threshold seems to be lower than 1 lux - which is extremely low.

LED professional: There is a map you can look at online where you can see night light all over the world and you can see how big the area is that is influenced by light.

Maja Grubisic: Most studies that we have by now look at the effects of direct light, but the indirect light or sky glow is of much lower intensity. There have hardly been any studies about light that scatters through the atmosphere and spreads hundreds of kilometers from the light source. We are running an experiment where we illuminate a lake with such low light levels, slightly higher than moonlight, which is of maximum 0.3 lux. So we illuminate the large experimental facilities in the lake with these intensities and then look at the whole food web, from microorganisms, algae, zooplankton, small moving invertebrates and fish, and we tried to see what it means to lakes that are in the surrounding of cities; how the lights from the cities influence their functioning.

LED professional: You have told us about the mechanisms and possible measures, so now it would be interesting to know what your future research plans are, the plans for the institute and what else do you think should be done? Also, how can conferences like this, along with industry, help in your work?

Maja Grubisic: This is a very dynamic field of research, we are just starting to understand effects of artificial illumination and there are still so many open questions. Any experiment that we do and the results that we get just lead to more questions. There are plenty of things that we have to study and I am personally interested in continuing work on this topic. I am currently involved in designing experiments at my institute and we are reaching out for funding and potential collaborators. This is a very interdisciplinary field that has a strong link to society and I think that experts from different industries could play an important role. The lighting industry can develop and test technical solutions for the ecological problems and they could also offer these solutions to the market. When it comes to ecological research, it is always the combination of laboratory and field studies because in the laboratory we can study mechanisms that are underlining certain impacts and in the field we can study what the real effects are on nature, in the complex systems where species interact and are influenced by many factors. This research is very relevant from an ecological point of view, but it is also very expensive because the building and the infrastructure is expensive: We have to go to dark areas that don't have light at all, then we bring the lighting there to see the changes made to the environment. So collaboration with the lighting industry to test different light sources or different lamp designs could be one of the ways that we could both benefit.

For the institute partners and programs: I mentioned that we are involved with several networks with interdisciplinary approaches and experts from different fields that are interested in the subject of light pollution, preserving darkness, recognizing the value of darkness. We also make recommendations for the adequate use of outdoor lighting and we try to push those to become policy. At the moment we are running a petition for better regulation against light pollution at the European level, because there are no laws concerning this issue at a European level.

Some countries have good examples of the national laws: for example, Slovenia has very strict regulations about lighting and they are a good example of pushing for dark sky friendly lighting - outdoor lighting that reduces light pollution, with lower impact on the environment and the visibility of the stars.

Early morning at a test site: Researchers collect insects at an experimental field in a remote rural area to study effects of street illumination on insect populations

Early morning at a test site: Researchers collect insects at an experimental field in a remote rural area to study effects of street illumination on insect populations

LED professional: It might be a good idea to move from Human Centric Lighting to Life Centric Lighting!

Maja Grubisic: Absolutely! I was positively surprised to see that there were so many talks about human centric lighting and the circadian rhythms at this conference. I think that if importance of lighting is slowly being recognized for humans, then perhaps there is hope that we will recognize its importance for other organisms and ecology as well.

LED professional: It is important that people like you keep coming to these types of conferences to boost awareness of this topic.

Maja Grubisic: I completely agree. I was very pleased to have been invited and given the opportunity to talk about the ecological perspective of lighting at the industry-focused conference. I learned a lot by attending the talks over the last couple of days. I think it's very important that our two communities communicate to each other because only by working together we can address this issue which affects us all.

LED professional: Thank you for taking the time to come to Bregenz and for consenting to this interview.

Maja Grubisic: Thank you.

Maja Grubisic

As a biologist, Maja Grubisic has been active in research on light pollution since 2013. She completed her Ph.D. studying ecological effects of artificial light at night on aquatic organisms at Freie Universität Berlin and University of Trento, and since has expanded her research to terrestrial ecosystems. Maja co-chaired a working group within the EU research network "Loss of the Night-LoNNe" (http://www.cost-lonne.eu/) from 2014 to 2016. From 2010 to 2013 she worked as a research and teaching assistant at University of Belgrade. Dr. Grubisic is currently working at Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) in Berlin and as a guest lecturer at Freie Universität Berlin.